Fitbit: My Brief Experience

In this post, I discuss my experiences using the popular Fitbit fitness tracker.

My Time With Fitbit #

I started using the Fitbit Ultra on April 11, 2012:

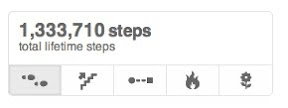

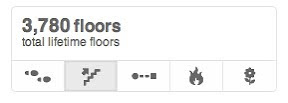

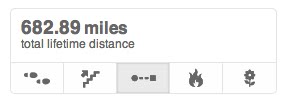

Over the following three months, I walked, ran, and otherwise jostled my Fitbit about a good deal:

Somewhere around July 12, tragedy struck: I lost my Fitbit.

The Good #

My initial impression was ecstatic. Fitbit didn't look like your average pedometer:

It was small, sleek, easily concealed. I felt like I'd stumbled upon the access key to some secret cult of digerati hipster fitness fanatics. I could flash my Fitbit, give a knowing nod - "yes, I too take an informed interest in my personal health" - and be accepted into the ranks.

Wireless syncing and long battery life sweetened the deal. This was a vast step up from my pen-and-paper recovery journal. I was doing serious self-tracking with serious devices now.

As I started to use it, I noticed small changes in my behavior. I'd walk an extra few blocks to the employee shuttle. I'd buy fewer groceries at the market, forcing myself to walk there more frequently. I'd take late-evening walks if I felt my daily step count was too low. Each change was minor, but they often added up to thousands of additional steps per day.

I'd also revel in more extreme bursts of exercise. A hike in the Marin headlands netted me the 30 000 step badge. I pocketed the 200 floors badge after a ride up to Tilden.

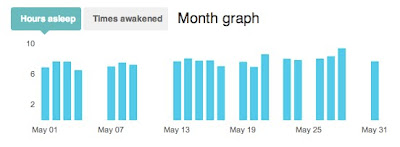

For the first time, I could also see how much I was sleeping:

Great gouts of data poured into my life, chartporn galore for an unrepentant math addict. Soon it even became a quasi-social activity as my leaderboard filled up with my Fitbit-using friends.

All in all, the Fitbit seemed like a fantastic way to turbocharge my exercise patterns.

The Bad #

My wife, Valkyrie Savage, also had a Fitbit. In the instructions, women were suggested to wear the Fitbit on their bra strap for the ultimate in clandestine self-tracking. This soon unearthed a glaring problem:

Sweat is corrosive to metal.

In particular, the internal leads started to corrode, and before long she was unable to connect it to the base station. After a quick phone call, Fitbit agreed to replace the device at no cost; we weren't the first users to have this problem, and they were in the process of changing the documentation.

Still, the experience soured the deal a bit. Had they never field-tested it with women?

While we waited for the replacement, I noticed something else: my wristband had stretched out and was now loose on my wrist. This was a minor detail, but it added to a growing concern that the Fitbit Ultra might not be durable enough to withstand our protracted Savage-ing.

Her second Fitbit finally arrived, and we were back into the self-tracking groove. We took our Fitbits everywhere: walking, running, playing soccer, cycling, and...wait, no, Valkyrie couldn't take it swimming. Actually, it didn't measure our cycling accurately, it was useless for my static bodyweight exercises, and it couldn't track our occasional indoor climbing stints effectively either. It was discouraging us from doing the activities we loved most!

The Ugly #

As we kept up our co-tracking, Valkyrie and I noticed a curious effect. There were several days where we spent the whole day together doing the exact same things, and yet I would always be 1000-2000 steps ahead. Our stride lengths and heights are nearly equal. What was going on?

We tried wearing the Fitbits in the same locations on our bodies. No effect. We tried counting steps while we were out together. The counts matched up. The solution came by accident. With the wristband getting more stretched out by the day, I finally started taking my Fitbit off when going to bed.

Aha! There was the difference: it was counting every tiny movement I made while asleep. This effect was never mentioned in the manual. It hadn't occurred to us that our data might not be comparable!

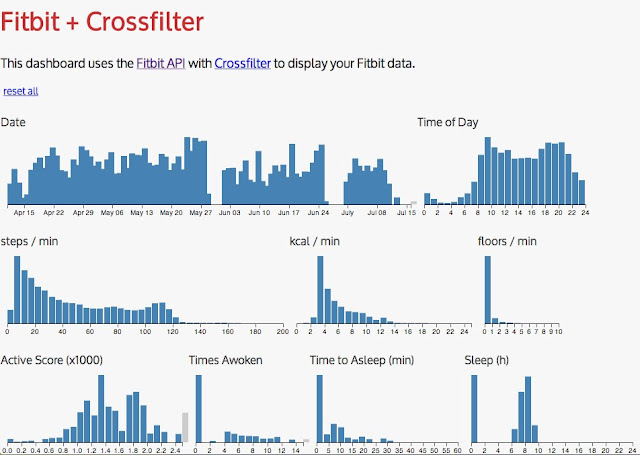

Meanwhile, my interest in Quantified Self was gradually intensifying. I decided to check out the Fitbit API, hoping to create something like zeo-crossfilter for Fitbit. This immediately hit a snag: to get the minute-by-minute data, you need Partner API access.

Partner API allows to fetch the intraday data points with 1 minute detail level for several user resources

Fortunately, Pavel Risenberg happily extended this access upon request, and I soon had fitbit-crossfilter up and working.

Again, though, there was that sour taste. Why not provide this access by default? A bit of digging around the site revealed a likely culprit: Fitbit Premium. Users can pay to turn Fitbit into a personal trainer, gaining access to more powerful data reports and goal-setting tools.

The Verdict #

Was the Fitbit useful for me? As a way to encourage walking: definitely. As a lightweight persistent self-tracking device: mostly. As part of an exercise program that meant something to me: not really.

I was left with a strong suspicion that I wasn't in their target demographic. I was already fairly active. 10 000 steps was more of a baseline than a goal. I didn't really need to walk more, and I couldn't trust it to accurately track the types of exercise I enjoy most.

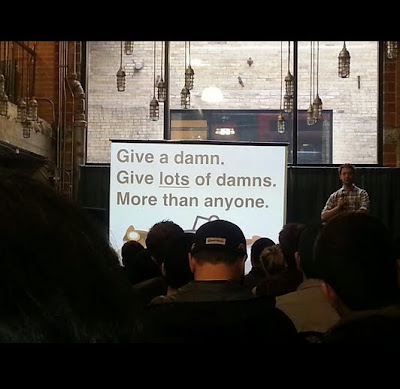

This is an important lesson for aspiring Quantified Self entrepreneurs:

Your product is personal by nature.

Your product will encounter different behaviors, needs, and goals. You are not everyone. You will never understand most of these behaviors, needs, and goals firsthand. No amount of user studies, A/B testing, or market research will save you from this fundamental truth.

The only way out is to give users control. Let them tinker, mashup, share, and explore. Let them decide what your product means to them.

Questions From My Time As A Fitbit User #

Who Owns Self-Tracking Data? #

Looking back, one of my largest complaints was about closed-ness. Part of the Grand Promise of Quantified Self is control over your data and how you use it. We're still a long way from that Grand Promise. We're in the Internet Middle Ages, an era of data fiefdoms.

The analogy is apt. Much as the old fiefdoms laid claim to your land and labor, these fiefdoms use your data and your data entry labor to enrich themselves. Much as the old fiefdoms provided vital services in exchange for this taxation, you receive the benefit of services like search and social networking. Much as the old fiefdoms fought each other relentlessly for economic gain, these fiefdoms wage war over users and intellectual property.

This is not necessarily bad. As a result of these data fiefdoms, we have many services that might not otherwise exist. By selling your self-tracking data back to you, Fitbit is able to fund the provision of tools for managing and improving your fitness. Those tools are generally of reasonable quality, and are likely to improve over time.

However, if you want to make your own tools, you're largely out of luck. You can pay for different tools via Fitbit Premium, but there's no guarantee that those tools will be better for you. Your only other recourse is to navigate the API documentation and contact the right people for better data access. Even with that access, you still only have minute-by-minute data. You have no idea how Fitbit maps between raw accelerometer readings and steps, and definitely no opportunity to improve that mapping. To take my example, I can't tweak the step detection algorithms to measure cycling accurately.

Even though the average person won't care to make these improvements, a few people will. This recalls the reddit maxim:

There's a tension here. This is how better products are built, but it's not in Fitbit's interest to let just anyone do that in a completely unconstrained fashion. If they do, they go out of business.

What Is My Ideal Fitness Tracking Device? #

It would be:

- activity-agnostic, with the ability to track diverse forms of physical activity.

- water-resistant. (I won't ask for waterproof, since I'm not much of a swimmer myself, but it should be able to handle light rain and a little sweat.)

- data-transparent, allowing me to get at the raw data without going through a vendor API. (I note that libfitbit exists as an attempt to reverse-engineer Fitbit, but I haven't played around with it.)

I haven't looked into BodyMedia or Fluxtream, but they both look promising.

Is Persistent Tracking Useful? #

Yes, but only if you can analyze the data as quickly as you generate it.