Adventure Games

We were suuuuuper excited about the recent release of Thimbleweed Park, which bills itself as a "new classic adventure game". From their website:

Welcome to Thimbleweed Park. Population: 80 nutcases.

A haunted hotel, an abandoned circus, a burnt-out pillow factory, a dead body pixelating under the bridge, toilets that run on vacuum tubes... you've never visited a place like this before.

Five people with nothing in common have been drawn to this rundown, forgotten town. They don't know it yet, but they are all deeply connected. And they're being watched.

In a town like Thimbleweed Park, a dead body is the least of your problems.

I've always been a big-time adventure game buff (to the point that I have a tattoo of King Graham's adventurer's cap), and I had a copy of Thimbleweed park reserved long before it came out. I followed their development blog religiously. The day the game came out, we sat down to play for several hours. We also played several more hours over the weekend that followed. We elected to try the "Hard" mode, which features all the puzzles, as opposed to the "Story" mode, which cuts many of them.

It was... kind of a bummer.

Don't get me wrong, it isn't a horrible game. It's actually been extremely well-reviewed (4/5, 9/10, etc., all over their main page). It has some funny stuff in it. This is a game that recognizes that it's carrying the banner of a lost art, and contains a healthy dose of self-referential humour to that effect. In keeping with the age-old inter-studio adventure game battle, it also pays lip service to Lucasfilm games and how they don't allow dying (as contrasted with Sierra and other adventure game-makers). It's got a fresh design aesthetic, though it keeps the pixels and the 9-verb interface from days of yore.

But the game designers make some assumptions that don't seem to be true anymore. The most important one here seems to be that these sort of item-shuffling exploration games are truly the best we can do as far as simulating adventures. Another one is that dying in games is bad. Finally, there's that 9-verb interface.

Adventuring and Item Games #

Back in the 1970s and '80s, adventure games grew out of the booming role-playing industry and the desire that fed it: to be someone else, doing something else, for a little while. The appeal of games like Dungeons & Dragons is that you, the player, have full control over the activity of the game. However, along with this comes a management system that is still considered too complicated for most people to pick up. It didn't take long for people to integrate this system into computer games: for obvious reasons it's much easier to play a D&D-based game than it is to manage a tableful of dice with varying numbers of sides. This also loses out on the total freedom that can come from having a human control the game system, but role-playing-type adventure games today are really popular. Final Fantasy. Deus Ex. Persona. World of Warcraft. Neverwinter Nights. The Elder Scrolls.

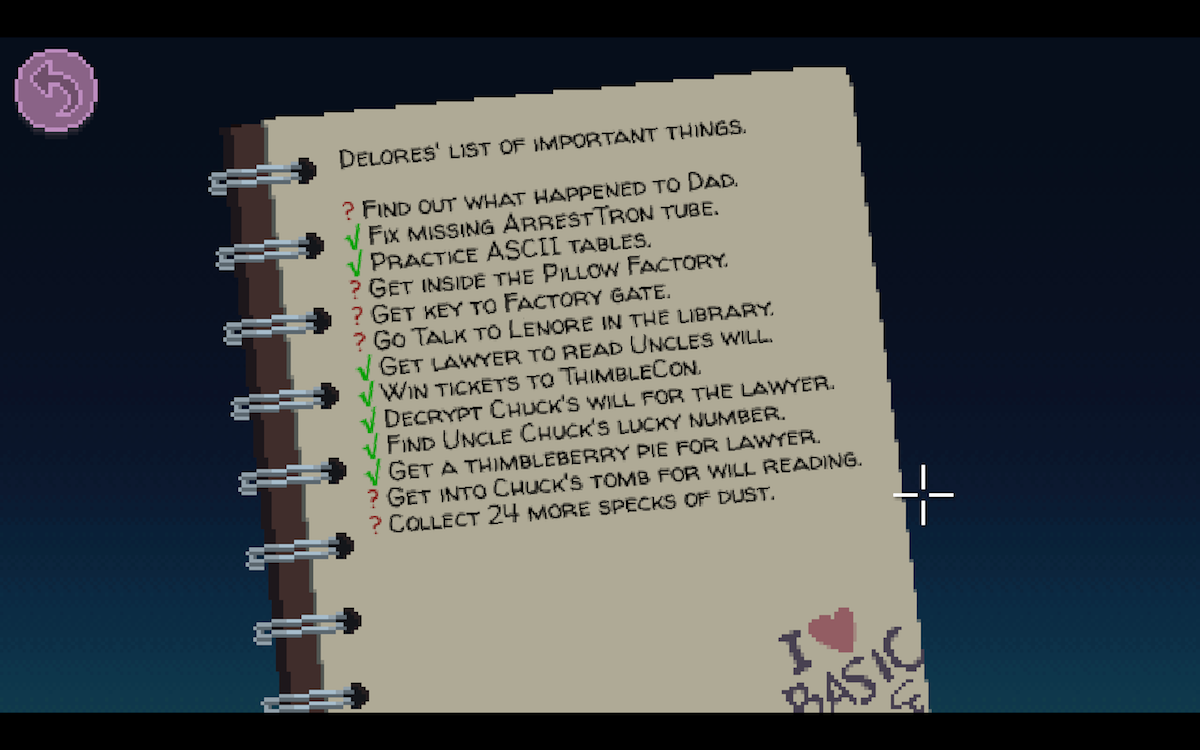

So what's the difference between a modern role-playing game and a classic adventure game? They both have "quests", in some sense. Thimbleweed Park very helpfully tracks these in a journal held by each of its playable characters:

This is a definite interface improvement over early adventure games (I remember my grandpa's notebooks filled with scribbles about puzzles still to solve), but it's basically the equivalent of quest logs in modern RPGs.

Both kinds of games also tend to have a small number of types of quests: the most common one in adventure games is the "Delivery Quest" (you can see the rest enumerated, for example, on mmorpg.com). This is not a quest type I love. It basically asks a player to find a particular object and bring it to a particular person. In adventure games, this often involves some kind of intermediate processing ("I don't want a blue catfish, you have to paint it red first!").

So... are these kinds of quests still the best way we have to simulate adventuring?

This question seems especially sticky since we got our first chance to play The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild over the weekend. It foregrounds a different kind of game system, where environments are based around physics rather than around pre-determined interactions. You can cut down a tree, and watch it roll downhill to destroy your enemies. When you're walking up a steep slope, if it becomes too steep to walk, your character will start climbing instead. If you grab a wooden club, you can set it on fire, and this can end in tears if you are careless about swinging it in long grass (yes, we did die in the game from a wildfire of our own creation, whoopsie).

I don't have an answer here, but with new kinds of games available it seems that the "adventure game" moniker feels a bit out of date.

Dying and The Stakes #

One feature heavily pushed by in-game jokes as well as on the Thimbleweed Park development blog is that this game is designed without dead ends. The designers describe what they see as two typical problems with classic adventure games:

- it is possible to not pick up all necessary items, pass through a "gate," and find yourself in an unfinishable game state.

- you can die.

The first issue is definitely a closely-held frustration for me. I once almost finished KQVI... only to realize that I hadn't sent a message with a nightingale approximately 2.5 hours previously and was now unable to defeat the final boss.

But what about that second thing? Is dying really so bad?

Certainly it can be. Classic adventure games handed out the death penalty for seemingly-small things:

- walking into an inn

- eating a pie

- typos

- killing a snake

If you fell to one of these happenings, you were left to reload such saves as you might have and play on from there. That's not very nice, but in today's world of auto-save it's not such a big deal (as long as you've already dealt with issue 1).

There has been some discussion on the web (for example, Kotaku) about whether dying in video games already means too little. The stakes are low when dying is meaningless (or even not present). Wandering around Thimbleweed Park, we found ourselves feeling a total lack of tension. Why should we be driven to solve this mystery? There isn't time pressure of any kind. There's no reason we shouldn't just click on everything, or say rude things to the townspeople, or try to accomplish ridiculous feats with the chainsaw. In a game where there is no death and no way to lose... well, where's the fun in that?

The Frustrations of 9-Verb interfaces #

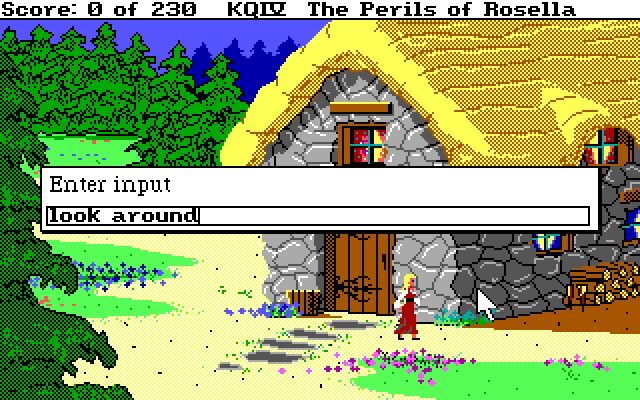

Adventure games started as pure text, but grew into graphical adventures as technology allowed. The original, Colossal Cave Adventure (or, simply, "Adventure"), was purely text. By the time my dear King's Quest IV came out, interfaces mixed text and the keyboard for input. This had the cool feature that you could try a huge variety of things, and the frustrating feature that the computer didn't understand most of them.

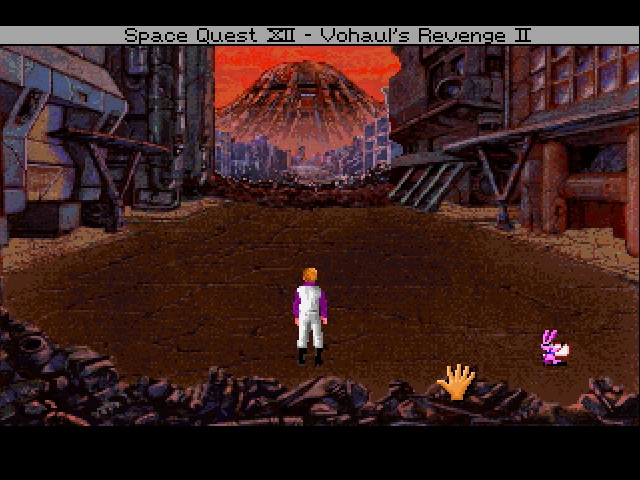

A bit later, developers experimented with a verb-based interface that was triggered with the mouse. In Space Quest IV (the SQXII in the screenshot is an in-game joke), input was through clicking on various objects. You could change the "verb" you employed by right clicking, or by hovering over the title bar and selecting the verb once the list appeared.

Thimbleweed Park, as you saw, uses the 9-verb interface that became more-or-less standardized around 1990. Open, Close, Give, Pick Up, Look At, Talk To, Push, Pull, and Use. Walking is triggered by clicking without selecting a verb.

Trying to use the elevator in-game is a classic "adventure game moment". A right click opens or closes the elevator when on the doors, a right click looks at the elevator when it is open and the cursor is not on the doors, and a left click walks. Ideally, to get in the elevator, you right click, then left click. We have gotten this wrong many times, and been treated to hearing each and every character tell us what an elevator looks like. Or closing the door when we meant to get on. Etc. It wouldn't be an adventure game without some usability problems.

But, really, why do we have this interface? With any given on-screen object, there are only a few things a player would conceivably want to do with it. I don't want to "look at" the path offscreen to the next site. I don't want to "pull" the hotel manager. Having more sensible defaults on mouse buttons (which could adapt per-item for maximum sensibleness) would feel liberating here. Modern console games typically get away with a single button that means "interact". This might lose some of the subtle interaction possibilities that are part of the adventure game canon, but most of those failed interactions are just annoying, and don't even have dedicated jokes or animation (the generics: "Why would I want to do that?", "I'm not putting my lips on that", "What would you do with it if you had it?").

Concluding #

Adventure games aren't sole heirs to the throne of adventure any longer. We now have better ways to feel like we're questing, ones without deliberately obtuse quests, with more tension, and with more satisfying interfaces. I'm not sorry we picked up Thimbleweed Park, but it wasn't all I had dreamed it would be.

- Next: Stardew Valley

- Previous: on blogs