Stardew Valley

Mental health is a difficult topic to handle in any medium, and for that reason it's rarely addressed. So when I started playing Stardew Valley, I was surprised to find that it deals openly and inclusively with mental health issues. From depression to PTSD to alcoholism to social anxiety, you'll get to know characters across the whole spectrum of DSM classifications, and you'll have a really great time doing so.

Aside from its willingness to break through the stigma surrounding mental health issues, Stardew Valley is also a really great game. Of the 60 or so games that came in the Humble Freedom Bundle we purchased a while back, Stardew Valley is by far the one we've played the most, and I'll get into why it keeps drawing us back.

But first, a screenshot from old SNES classic Harvest Moon:

And here's Stardew Valley:

At first glance, Stardew Valley is Harvest Moon 2.0. Both are farming simulation games, and they share a lot of the basic mechanics. Both have you grow crops and raise animals to produce goods that are then sold to help grow the farm. Both have similar systems of time, with hours of the day and a four-season calendar complete with festivals and NPC birthdays. Speaking of NPCs, both allow you to befriend them by giving gifts and talking to them, and both allow you to marry NPCs that you've reached a high enough level of friendship with. Both have upgradable tools, stamina to limit how much you can do in a day, fishing, house upgrades, and so on.

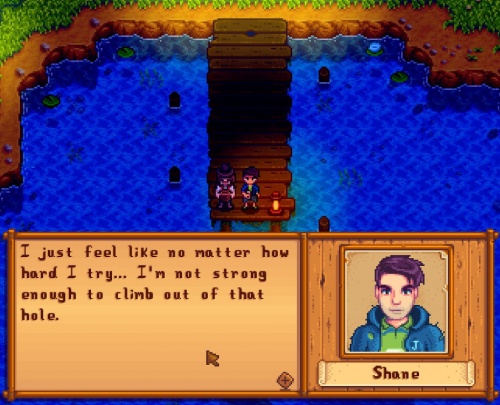

So what's different? Well, there's the mental health thing, for starters:

This interaction, which happens once you reach the two-heart friendship level with a villager named Shane, is a strikingly open discussion of depression in an otherwise cute and colourful game world. Before you reach this level, Shane will push you away whenever you try to speak to him. You learn gradually that Shane self-medicates with alcohol, but it doesn't help. You also come to see that he has a passion for raising chickens. It's a great example of how, by taking a game mechanic (friendship) and raising the stakes, you make that mechanic much more compelling. You're helping these people work through their issues as you get to know them; the flip side of that, of course, is that you can only people whom you interact with, so failure to interact takes on a moral / ethical dimension. It also encourages empathy for the characters: even if you wouldn't normally like their personality, chances are good they're fighting a battle you know nothing about.

The same is true of the broader community, which is being eroded both by neglect and by the appearance of mega-corporation Joja in town. Early on, you're presented with a choice: do you help tiny Kodama-like spirits rebuild the community centre, or do you sign up for a JojaMart membership and turn that centre into a Joja warehouse? You can, of course, make either choice, and they lead to different modes of gameplay. The community centre path requires you to deliver various items, and encourages a more exploratory play style. The JojaMart path instead depends on constant infusions of money, which leads to a more optimized / micro-managed play style. Since crop seeds cost more at JojaMart, this is also cleverly balanced to double as a "hard mode" after you complete the game: most players will pick the altruistic community centre path their first time.

This "hard mode" balancing is just one example of how Stardew Valley encourages mastery learning throughout. Another great example is the fishing minigame:

Once you hook a fish, you enter a minigame where the fish bobs and jumps around this track while you try to keep the yellow bar underneath it. You gradually learn where to find different species and how they move along this track, to the point where you can guess what you're catching before you actually catch it. If you're following the community centre path, this knowledge becomes vital in tracking down the fish you need to deliver.

Stardew Valley also adds a combat system, where you enter a sort of roguelike dungeon-crawling mode to find precious metals and other unique resources. Some of these resources can't be found anywhere else in the game, and the metals and resources alike help to build gadgets that improve your farm: automatic watering sprinklers, mayonnaise machines, etc. Speaking of sprinklers, those also appeared in Harvest Moon, but you simply bought them from the Tool Shop; by tying these upgrades to dungeon exploration, it really gives you that satisfying "I earned this the hard way!" feeling familiar to Survival-mode Minecraft players.

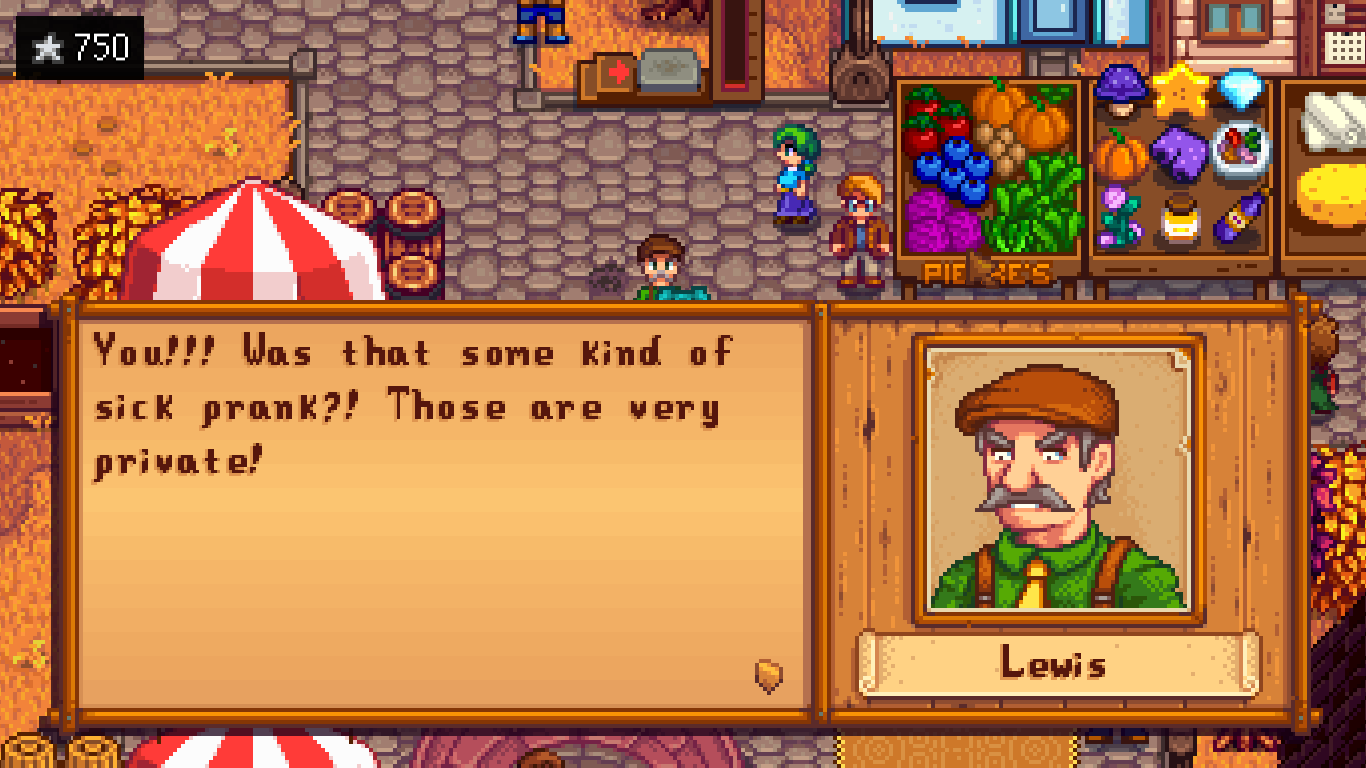

And, finally, Stardew Valley has some wonderful comedic moments, like when you find Mayor Lewis' purple underpants in Marnie's room and decide to add them to your grange display at the Harvest Festival:

So: not that this is a review, but if it were, I'd be telling you to go out and buy this game right now. Since it's not, though, I'll say that it's refreshing to see games tackling thorny subjects in increasingly approachable ways, and it's also amazing to see another successful and engaging simulation game!

- Next: Zombies!

- Previous: Adventure Games